Learning to Work Together: The Importance of Safety Drills May Take Some Time to Sink In

May 14, 2021 / by The “I Love U Guys” Foundation

Ryan Cothran has his hands full. His corner of the world, the upper South Carolina’s Spartanburg/Greenville area, is growing. His school district is in the process of building two new schools at a time when groups are facing the challenges of social gathering. As the Director of Safety and Emergency Services for Spartanburg District Five, the year 2020 threw him a curve, like it did for so many of us.

“COVID hit,” he told us, “and everything I planned to get done, didn’t get done.”

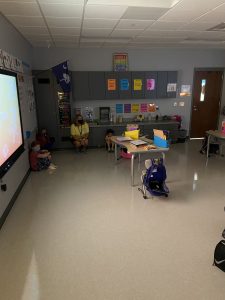

Now nearly all Spartanburg District Five’s 9,000 students are back indoors, learning between plexiglass, through masks, and six feet apart. And while they’ve been doing lockdown drills per the Standard Response Protocol (SRP) since Ryan started with the district, pandemic restrictions have required some learning and adjusting.

“We do four [drills] a year,” Ryan said. “We use [the SRP’s] exact terminology and process, and the students are used to going into their ‘hard corner’ (locks, lights, out of sight per the SRP) during the drill. With COVID hitting, one thing that was important to me was to make sure everyone still had the muscle memory. I didn’t want them to lose what we had developed.”

So despite the challenges, Ryan has his schools conduct their drills while maintaining social distancing, “realizing they aren’t going to get out of sight. Which is fine.”

Learning and adjusting

Learning and adjusting. It’s what 2020 and 2021 have been all about. The challenges of the pandemic have helped us all remember that The “I Love U Guys” Foundation’s protocols, while based on research and best practices from school and community safety practitioners, are living and breathing systems, still relatively new in their development. And since the environment dictates the tactics, like when it plays host to a pandemic, we’ll continue to take in new data and improve those tactics.

Learning and adjusting. It’s what 2020 and 2021 have been all about. The challenges of the pandemic have helped us all remember that The “I Love U Guys” Foundation’s protocols, while based on research and best practices from school and community safety practitioners, are living and breathing systems, still relatively new in their development. And since the environment dictates the tactics, like when it plays host to a pandemic, we’ll continue to take in new data and improve those tactics.

An example cited by Ryan is the one reported in a recent national article on lockdown drills in New York City, with kids staying “in their seats and [remaining] silent instead of moving to the safe corner.” We’ve heard from other schools that are asking kids to move one at a time to the safe corner to keep the muscle memory activated.

To some, the new and unfamiliar can breed a degree of fear, a dynamic most commonly manifested when we talk about safety drills. We’ve written about this extensively. From researchers demonstrating the efficacy of drills and the experiences of parents watching muscle memory kick into the history of fire drills as examples of how lives can be saved, lockdown drills are a critical element of safe schools and that’s why they’re recommended in the SRP.

“There’s no need to simulate or even describe the danger of a crisis in order to develop the muscle memory necessary to react to them.”

Ryan and others know this, and are conscious of conducting them regularly and without trauma, which is where critics tend to focus their attention. Even if lockdown drills are new and are dealing with the kind of threat that can activate our deepest fears, we know how to create trauma-free drills. We do it all the time for fire and other emergency drills (like tornadoes), which Ryan says he conducts using essentially the same protocols as those outlined in the SRP. There’s no need to simulate or even describe the danger of a crisis in order to develop the muscle memory necessary to react to it. In fact, the SRP provides the fact-based, objective framework to have such conversations.

To avoid the trauma that could potentially come with lockdown drills, Ryan told us that “we just describe the SRP and the importance of it, and how it keeps people safe.”

It’s more nuanced than that, of course. Ryan invites law enforcement as guests to discuss their role and observe the SRP processes, and there are descriptions of what it might look like should law enforcement arrive during a crisis. But the foundation is simple: Stick to the words and terminology of the protocol.

Words matter

As the world gets used to life with safety drills, consistency with terminology matters. It’s one of the main themes of the SRP itself, but it’s also important on other school safety fronts. One of the more glaring examples of this is the conversation around drills, the difference between drills and exercises, and people using discussion of drills to instill fear instead of reflecting a dedication on the part of school safety practitioners to create a sense of safety.

We need to start coming together as a community to keep this in check.

There are many stories in the media that serve as clear examples. We recognize that media outlets may have different perspectives than we as a community do, and that they have a tendency to represent all sides. Still, when we see the loose use of drills and exercises interchangeably describing similar things, or using the fear of school shootings to engage the reader, it gives us pause.

In our world, we view drills as an opportunity to create “muscle memory” and we don’t simulate an event that would result in performing the action. In an exercise, an event is simulated to test the capacity of responders.

One recent piece in the national media questioned the mental health effects of “active shooter drills” throughout, which seems to us like describing or at least alluding to active shooter exercises. We advocate the use of “lockdown drills” or “drills” when referring to student-involved training in connection with our protocols, never “active shooter exercises.” Lockdown drills simply prepare us for any threat inside the school building using the objective and trauma-free terminology of the SRP.

One recent piece in the national media questioned the mental health effects of “active shooter drills” throughout, which seems to us like describing or at least alluding to active shooter exercises. We advocate the use of “lockdown drills” or “drills” when referring to student-involved training in connection with our protocols, never “active shooter exercises.” Lockdown drills simply prepare us for any threat inside the school building using the objective and trauma-free terminology of the SRP.

We recognize the inherent complexity when it comes to words, terms, and clarity of communications. It’s our day-to-day work of worry. So what may seem careless to us may just be a learning curve to others. Still, we all need to recognize there’s real risk in not getting the words right.

No one wants to gin up fear, but when the media cites something like the public criticism of “active shooter drills” from the American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association, and Everytown for Gun Safety without differentiating it, we’re concerned that it works against our efforts for consistent and clear dialog. For instance, they propose an unspecified “comprehensive approach” to “drills” that doesn’t involve students, but because of the inconsistent use of the term “drills,” it isn’t exactly clear what they’re proposing. Our view is that in order to be comprehensive, it’s essential to involve the kids. So let’s make sure we demand appropriate actions during any safety drill.

What we’ve learned from our community is that exercises, which are intended to train first responders, law enforcement, and school staff, are for the adults and should not involve kids. Exercises may involve scenario and tactical simulations that introduce some of the stress, distractions, and other randomness that actual crises generate. Kids should be left out of these for a number of reasons, the trauma they may create chief among them.

We’ve seen another media narrative about would-be shooters using drills to aid in their planning, and that this represents another reason to leave kids out of drills. But what we know from our friend Dr. Jaclyn Schildkarut (and others) is that there is simply no data to support the idea that drills somehow aid in the planning of shootings. We can all help dispel this myth with some compassion toward those processing the data, learning the new path we’re charting, and addressing it instead of letting it pass without comment.

“Kids learn. Their muscles remember. And they use them in a crisis.”

In the end, our protocols recommend regular drilling. The drills should be announced. There’s no need to describe a scenario, let alone simulate one, and they should be conducted even while maintaining social distancing. Kids learn. Their muscles remember. And they use it in a crisis.

And here’s the wonderful news about the kids we’re keeping safe: They’re smart. They understand that there’s uncertainty in the world and they want us to tell them that we care about them and are doing everything we can to keep them safe.

And here’s the wonderful news about the kids we’re keeping safe: They’re smart. They understand that there’s uncertainty in the world and they want us to tell them that we care about them and are doing everything we can to keep them safe.

As we all take part in conversations in our communities and communicate to kids and parents, drawing distinctions between lockdown drills and exercises is important to move our efforts forward productively.

We found a balanced opinion by a slate.com journalist in a piece about practicing drills in virtual school settings. The author quotes a parent after watching an “I Love U Guys” video who found it “was clear, age-appropriate, and non-sensationalized. (It’s narrated by a girl, now a teenager, who survived the Sandy Hook shooting when she was in fourth grade.) The experience was more traumatic to me in its concept than it was to actual children in its execution, a result I heard from other parents as well, like Menschner, who said, “I changed my tune a little. I felt it was handled well.”

We all have biases and room to grow and learn from one another. With intention and practice (and a little time) we can help our communities better understand lockdown drills and embrace them. We learn from things like pandemics, and from each small opportunity for dialog that comes into our worlds.

And we keep getting better.

Anyone can download our safety programs at no cost—not even an email—on our website. The “I Love U Guys” Foundation offers in-depth training and presentations for school safety gatherings, both remote and in person. Contact us for more details.

Learn more about The “I Love U Guys” Foundation, and follow the conversation on Facebook and Twitter.

Categories: All

Written by The “I Love U Guys” Foundation